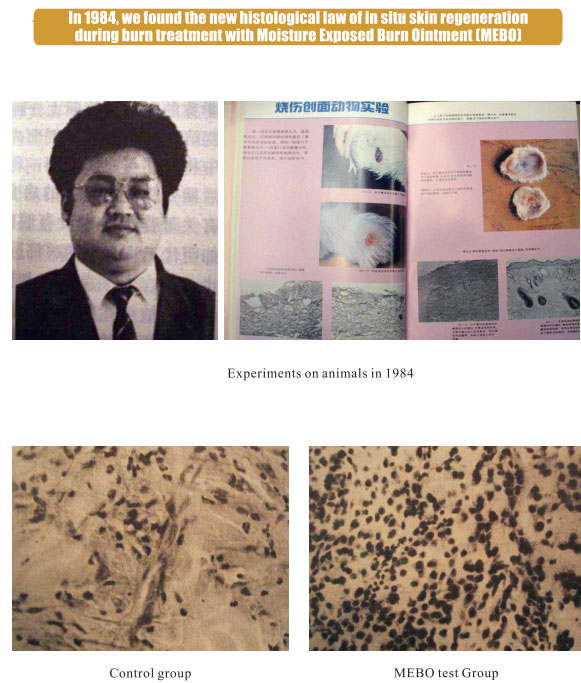

1. The earliest period of histological discovery

作者:Xu Rongxiang 出版社:CHINA SOCIAL SCIENCES PRESS 发行日期:2009 September

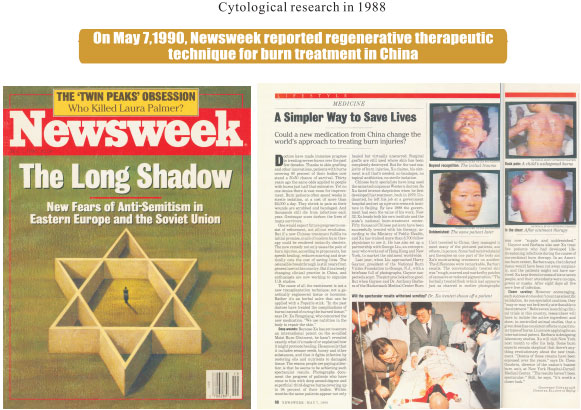

A Simpler Way to Save Lives

Could a new medication from China change the world's

approach to treating burn injuries?

Doctors have made immense progress in treating severe burns over the past few decades. Thanks to skin grafting and other innovations, patients with burns covering 80 percent of their bodies now stand a 50-50 chance of survival. Thirty years ago the same odds applied to people with burns just half that extensive. Yet no one denies there is vast room for improvement. Burn patients often spend weeks in sterile isolation, at a cost of more than $2000 a day. They shriek in pain as their wounds are scrubbed and bandaged. And thousands still die from infections each year. Grotesque scars darken the lives of many survivors.

One would expect future progress to consist of refinement, not all-out revolution. But if a new Chinese treatment fulfills its initial promise, much of modern burn therapy could be rendered instantly obsolete. The new remedy not only eases the pain of burn injuries, according to proponents, but speeds healing, reduces scarring and drastically cuts the cost of saving lives. The ostensible breakthrough is still years from general use in this country. But it is already changing clinical practice in China, and enthusiasts are not working to organize U.S. studies.

The cause of all the excitement is not a new transplantation technique, not a generally engineered tissue or hormone. Rather it's an herbal salve that can be applied with a Popsicle stick. “in the past doctors have treated the complications of burns instead of curing the burned tissues,” says Dr. Xu Rongxiang, who concocted the new medication. “We use nutrition in the body to repair the skin.”

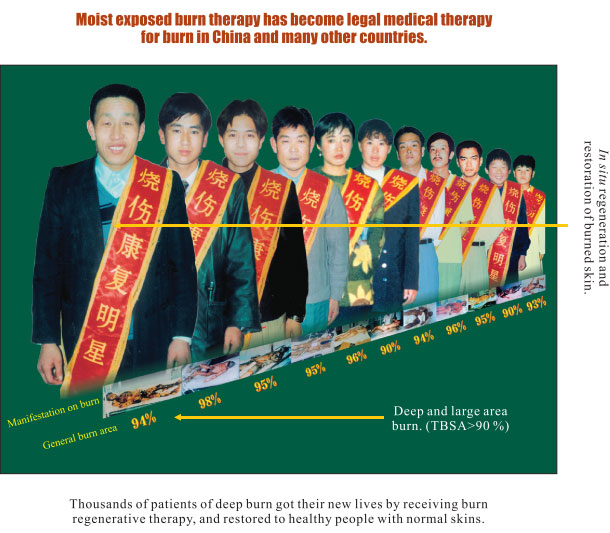

Deep wounds: Because Xu has yet to secure an international patent on the so-called Moist Burn Ointment, he hasn't revealed exactly what it's made of or explained how it might promote healing. He says only that it includes sesame seeds, honey and other substances, and that it fights infection by restoring oils and nutrients to damaged tissue. The reason people are paying attention is that he seems to be achieving such spectacular results. Photographs document the progress of patients who have come to him with deep second-degree and superficial third-degree burns covering up to 94 percent of their bodies. Within months the same patients appear not only healed but virtually unscarred. Surgical grafts are still used where skin has been completely destroyed. But for the vast majority of burn injuries, Xu claims, his ointment is all that's needed: no bandages, no topical antibiotics, no sterile isolation.

Chinese burn specialists have long used the same techniques as Western doctors. So Xu faced intense skepticism when he first developed his treatment, back in 1979. Undaunted, he left his job at a government hospital and set up a private research institute in Beijing. By late 1988 the government had seen the value of his work. Now 32, Xu heads both his own institute and the state's national burn-treatment center. Fifty thousand Chinese patients have been successfully treated with his therapy, according to the Ministry of Public Health, and Xu has trained more than 3,700fellow physicians to use it. He has also set up a partnership with Geroge Liu, an entrepreneur who works out of Hong Kong and New York, to market the ointment worldwide.

Last year, when Liu approached Harry Gaynor, president of the National Burn Victim Foundation in Orange, N.J., with a briefcase full of photographs, Gaynor suspected a scam. The pictures looked too good. But when Gaynor and Dr. Anthony Barbara of the Hackensack Medical Center Burn Unite traveled to China, they managed to meet many of the pictured patients, and others, in person. Some had received standard therapies on one part of the body and Xu's moisturizing treatment on another. The differences were remarkable, Barbara recalls. The conventionally treated skin was “rough, scarred and marked by patches of excessive or reduced pigmentation.” The herbally treated flesh (which had appeared just as charred in earlier photographs) was now “supple and unblemished”.

Gaynor and Barbara also saw Xu treat five patients who had developed life-threatening infections during the course of conventional burn therapy. In an American burn center, Barbara says, the infected tissue would have been cut away surgically, and the patients might not have survived. Xu kept them in rooms of six or seven people, and their attendants wore no caps, gowns or masks. After eight days all five were free of infection.

Closer scrutiny: However encouraging, such success stories don't count as scientific validation. As one specialist cautions, they “may or may not be directly attributable to the ointment.” before even launching clinical trials in this country, researchers will have to isolate the active ingredient and show, in controlled animal studies, that a given dose has consistent effects on particular types of burns. Liu is now applying for an international patent. Barbara is designing laboratory studies. Xu will visit New York next month to offer his help. Some burn experts remain skeptical that there's anything revolutionary about the new treatment. “Dozens of these creams have been espoused over the years,” says Dr. Cleon Goodwin, director of the nation's busiest burn unit, at New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center. “The results haven't been spectacular.” Still, he says, “it's worth a closer look”